Napirze: Drawing a Floodplain

Reclaiming a large-scale public landscape in Rustavi through different "drawing" methods, including GPS tracking, drone photography, traditional drawing, and brush cutting.

Auburn MLA Student and Ruderal Summer Research Associate Maggie Brand describes her work with Data Tsintsadze in planning, testing, and initiating landscape interventions in the Rustavi Floodplain to revitalize this critical public landscape. Their approach adapts the self-initiated, "replicable frugal, and malleable methods” of the Girona Shores1 project pioneered by Estudi Marti Franch in Catalonia. Tsintsadze describes the impetus for the floodplain project in a 2022 interview with Sarah Cowles. Napirze in Georgian means “On the bank” of a river.

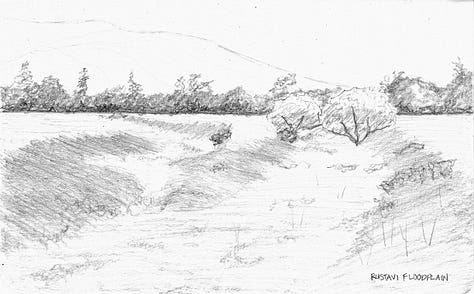

Three days after arriving in Georgia, I walked the Rustavi Floodplain with Data Tsintsadze and a group of interns (Ani Sadunishvili, Eka Khomeriki, Marika Verulidze, and Nini Oragvelidze) from Ruderal. By the end of the day, I was convinced we could make this place a haven for all in the heart of the city.

With the same spirit that drove the making of Data’s Garden, the floodplain became a place of “what ifs” and “why nots” – big dreams and simple actions.

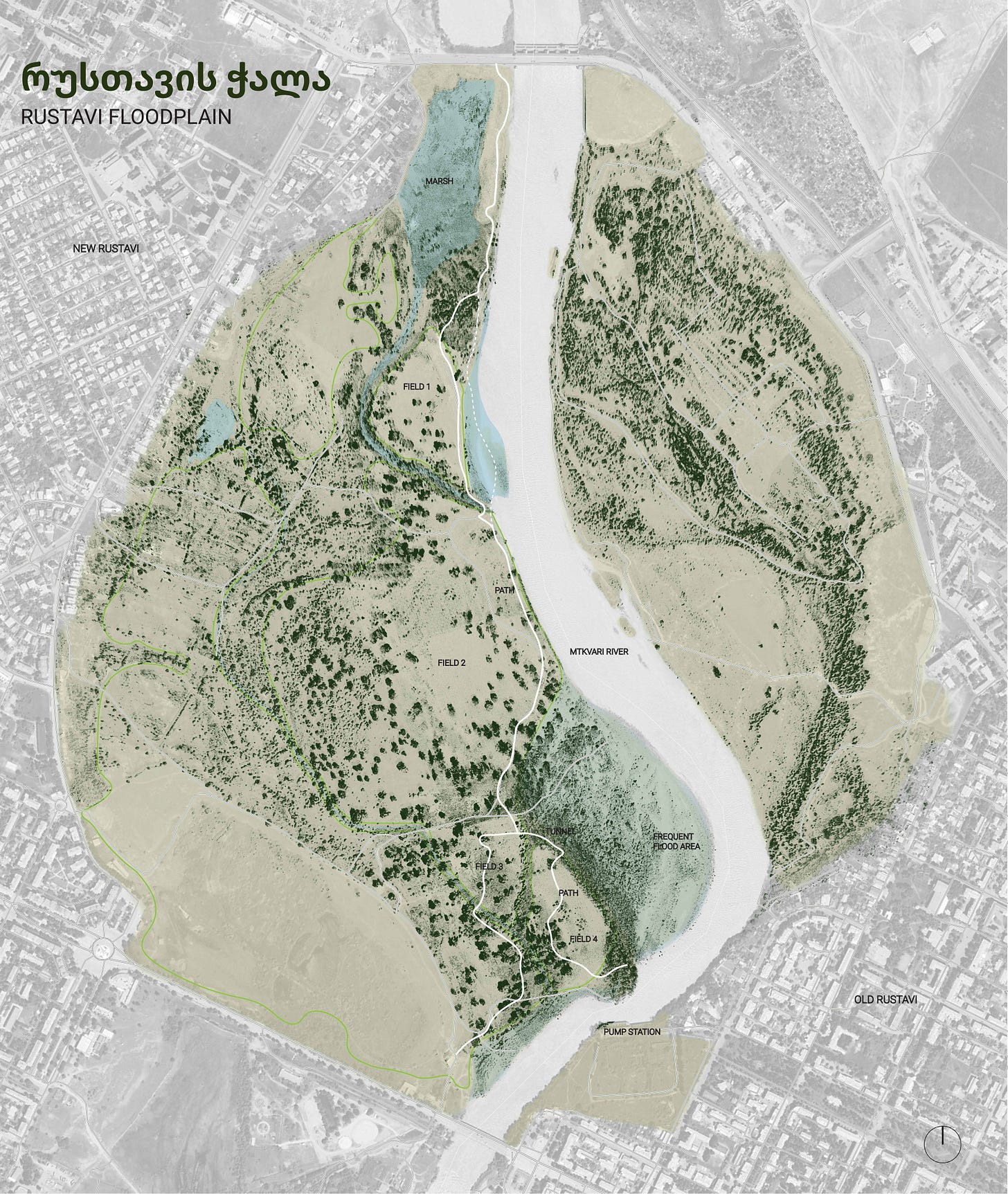

The floodplain covers 300 hectares of overgrazed, deforested river-bottom land between Old and New Rustavi. There are remnant channels and diversions, jeep trails, a few Populus trees, and a thick understory of tough Zygophyllum fabago (Bean caper).

To adapt this landscape to public use and increase ecological function, the Ruderal team studied the self-initiated, low-cost strategies for urban wildland revitalization developed for the Girona Shores project. They produced initial floodplain and urban context studies and developed programming concepts.

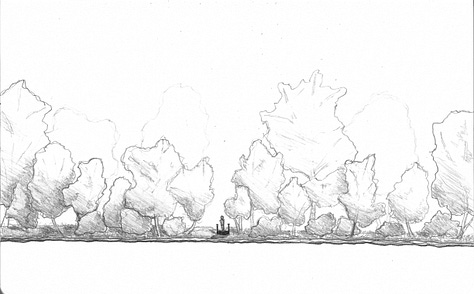

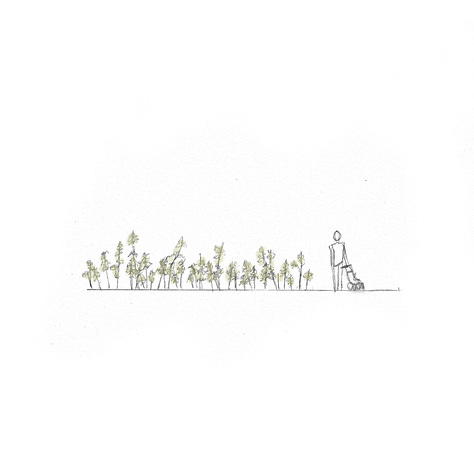

Tsintsadze spelled out the long-term vision for the future of the floodplain as a place of rest and play for residents of Rustavi. The first step involved creating paths for exploring the floodplain and connecting directly to the river. Creating this space would also bring opportunities for Tsintsadze to share his ideas for ecological restoration of the site, which include reforestation of the territory via the Miyawaki Method2, cleaning refuse and debris, and restoration of biodiversity.

Drawing 1: Initial site visit

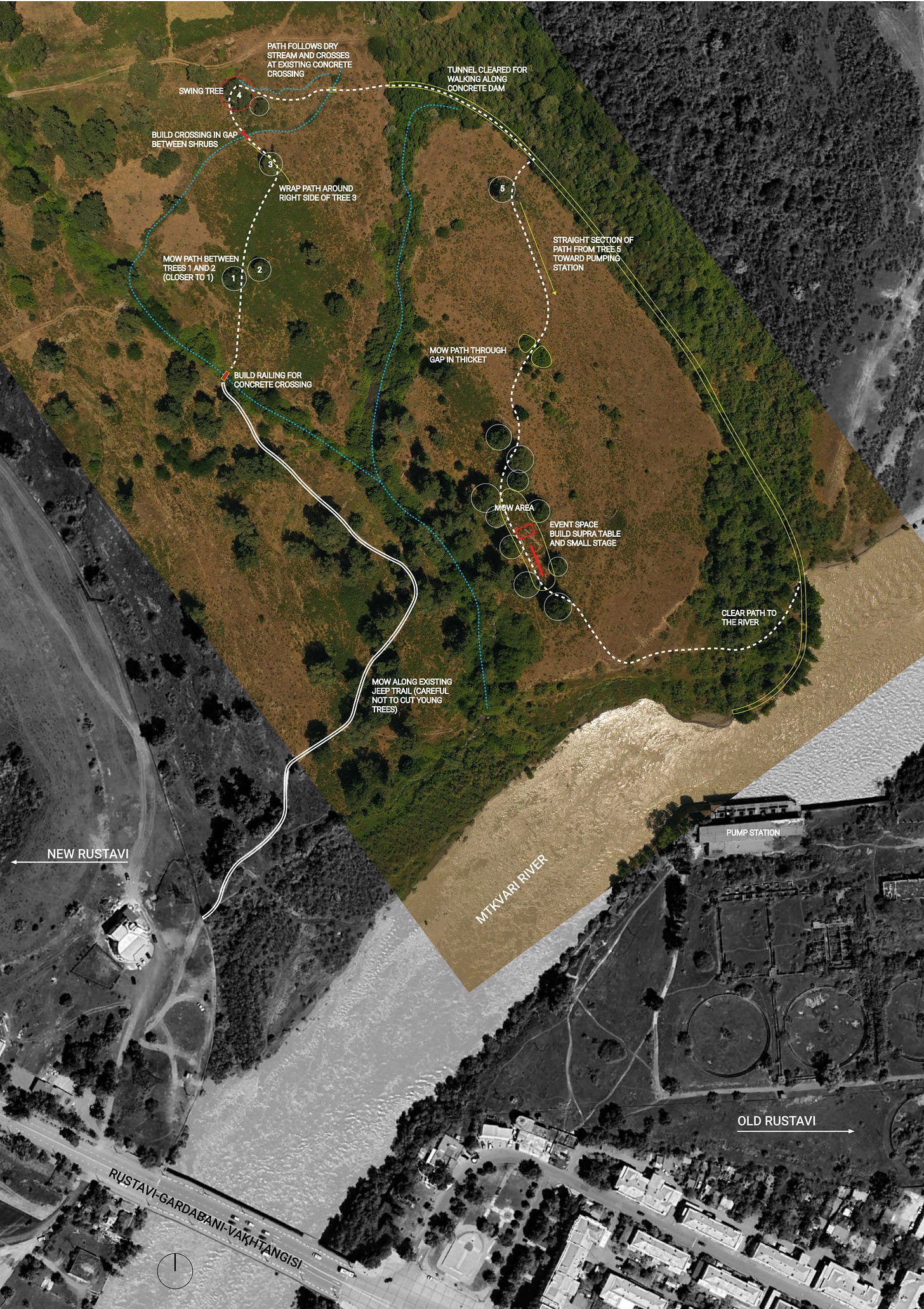

Our approach to designing a path in the floodplain was fueled by practicality and curiosity. How can we cross this stream? Why is there a concrete dam on the edge of that field? Does it reach the river bank? What viewsheds can be revealed? How are fishermen getting to the water’s edge? How does the topography work?

The route of the pathway was slowly revealed to us by the exceptional characteristics found on the site. We tracked our paths and points of interest with the Gaia and Garmin Connect apps and applied them to site our analysis, representation, and design.

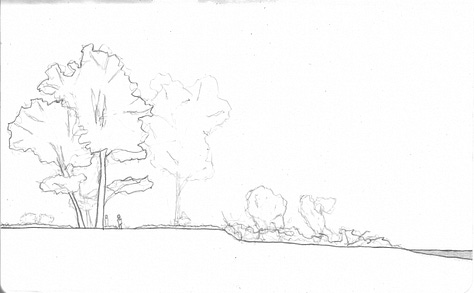

We took note of the old Populus trees casting shadows perfect for resting along the path. We recorded viewpoints and thresholds for dramatic experiential change and the existing jeep trails that weave through the trees.

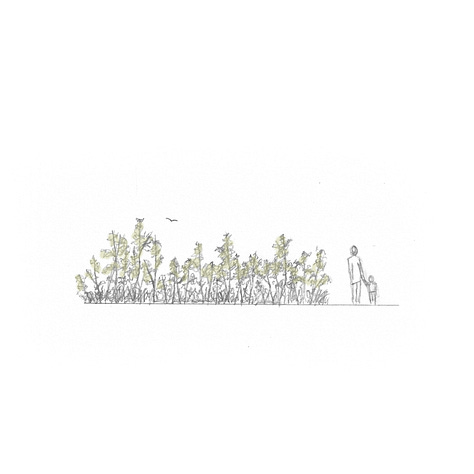

Drawing 2: Visualization

The next challenge in the project was to make instructional drawings for volunteers who would join us in making the path. Not knowing how many people would volunteer or what tools we would have, the drawings needed to display original design intentions while understanding that volunteers would be making design decisions on the ground - intentionally or unintentionally.

Drawing 3: Revisiting the site and expanding ideas

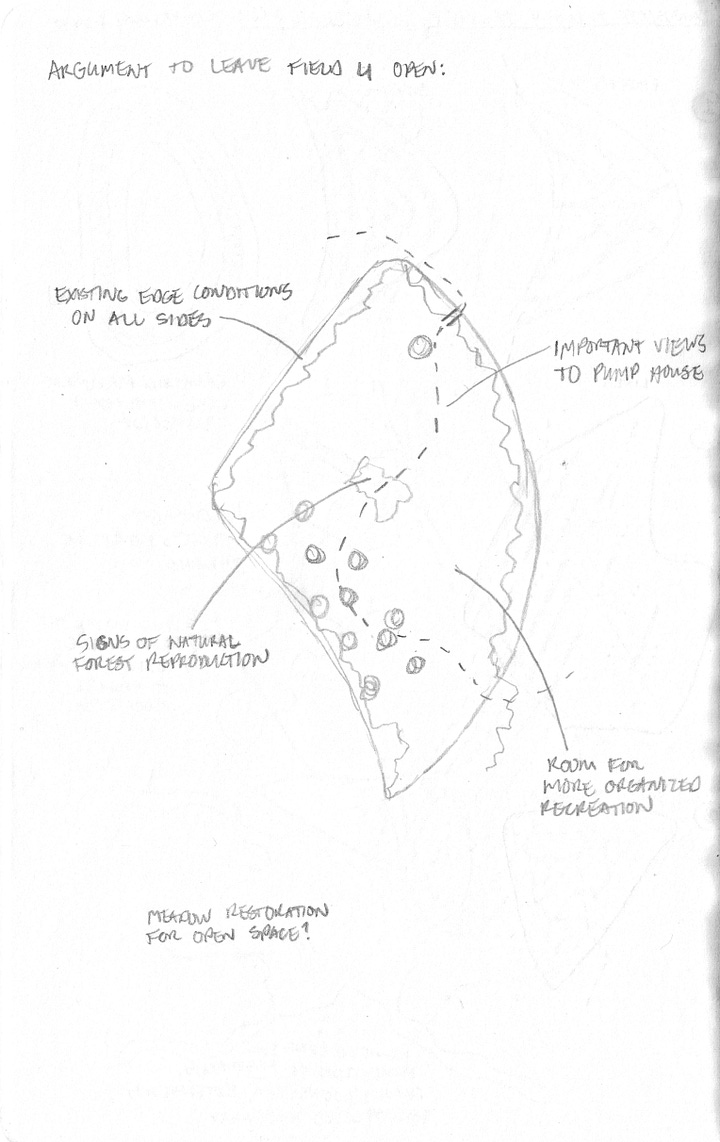

After receiving permission from the Rustavi Mayor to access the entire floodplain, we revisited the site to locate a path connecting the northern and southern bridges. We could follow an existing jeep trail that runs along the river bank. The path following the edge creates a starting point for engaging seasonal flood levels with secondary pathways.

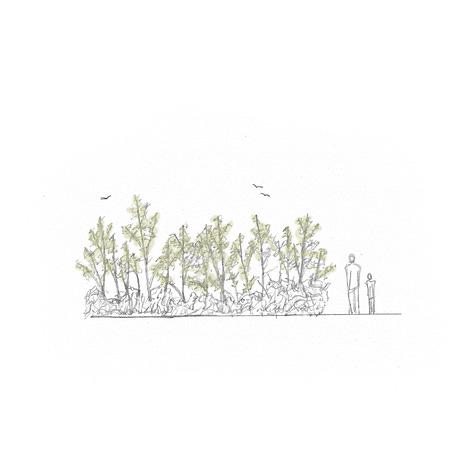

Drawing 4: Visualization

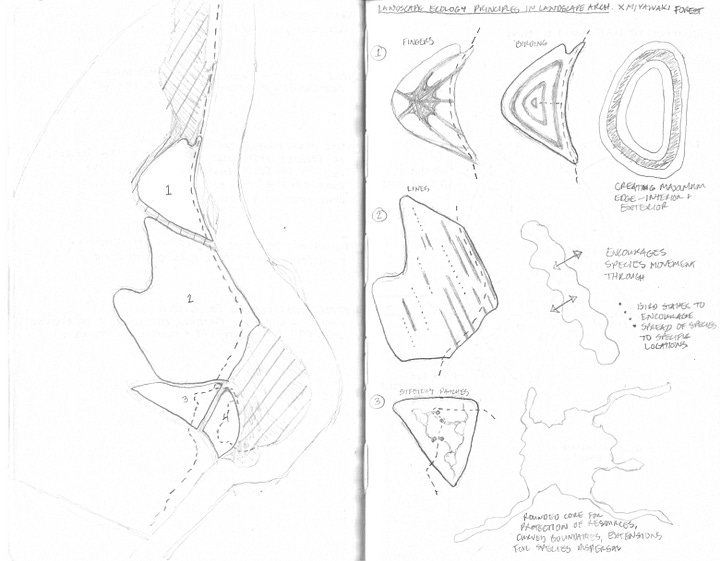

After this visit, I drew the extent of the floodplain by overlaying new GPS tracks with updated drone imagery. This drawing lets us map site zones and different forms of Miyawaki forest plots, which Tsintsadze will begin planting in the fall of 2023.3

Drawing 5: Mowing and Clearing

In mid-July, we began clearing the paths with help from volunteers from Rustavi and Tbilisi. The tools were minimal: a weed whacker from the city, a scythe, a rake, and a few hand-held clippers. Due to the gnarly habit of the vegetation and the limited tools, it wasn't easy to maintain path alignments.

The paths did not evolve exactly as planned, but they were made by the hands of people who truly believe in the ability of this island of a wildland in the middle of Rustavi to have a positive impact on the city and its people.

Drawing 6: The Event

On July 18th, we took the first group of people to walk the new path on the floodplain. Tsintsadze shared his vision and spread excitement for the future of the floodplain to people from Rustavi, Tbilisi, and beyond. This was a small step in the process, but it brought much excitement and joy to all who made it happen.

Big thanks to all involved who allowed me to play even a small role in this incredible effort.

https://landezine.com/lila-2020-gironas-shores/

The Miyawaki Forest Method is a technique pioneered by Japanese botanist Akira Miyawaki that involves planting dozens of native species in the same area close together to create dense, fast-growing, and sustainable mini-forests. The approach capitalizes on the natural growth competition among the diverse trees to yield a rich, resilient ecosystem that can achieve maturity up to 10 times faster than a conventional forest.

UNDP GEF Small Grants Program funds this project.