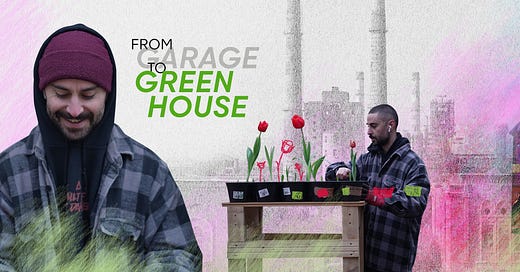

From Garage to Greenhouse

A conversation with Data Tsintsadze, founder of Data's Garden in Rustavi, Georgia

We are gathering stories of environmental optimism, perseverance, community-building, and experimentation in Georgia and the region. Let us know about projects or people making a difference in the local environment by sending us a direct message via our Instagram account.

Data Tsintsadze is the founder of Data’s Garden in Rustavi, a city south of Tbilisi. Tsintsadze is an environmental leader, community organizer, and gardener. An accomplished production cameraman, he leverages his experience in media and communication to focus public attention on environmental justice issues in Rustavi.

I was introduced to Tsintsadze’s work several years ago via his Instagram account, Suckingupsun. At that time, he posted hazy clips of Rustavi’s edges, smoggy skies, former factories, and crumbling infrastructure. Since 2021, it is a chronicle of his work building Data’s Garden, and film screenings and workshops he hosts there. And the feed includes setlists for the Tbilisi club Left Bank, where he bartends to support his community work.

Tsintsadze’s activism and activities are rooted in his hometown of Rustavi. Rustavi was developed as a monotown for steel production in the Soviet era. Only a handful of large plants–cement, fertilizer, and metallurgy–operate in Rustavi, with minimal regulation. Residents of industrial cities in Georgia endure the legacy effect of Soviet-era industrial contamination and pollution from the deregulated industries of today.

This December, Kim Cordova (visiting artist, Tbilisi Architecture Biennial) and I met with Tsintsadze to discuss his environmental activism, community work, and future projects.

SC: Tell us about your work in Rustavi.

DTs: I’ve been a cameraman for Georgian TV since I was 17, so for a total of nine years. My friend started a movement in Rustavi called “Gavigudet” to bring attention to air pollution in Rustavi. Even though I grew up here, I did not know the extent of the air quality issues. I joined the movement in 2019 and used my professional knowledge as a cameraman to communicate the scale of the problem. We made a film about the industrial zones and screened it for the community. After the screening, we created a space in the front yard of my house. We did live streams of electronic music with the films from the industrial zone. We were not doing it for traditional or social media– it was for the community. I like to make things spicy with culture and art. It is how I am comfortable protesting and making changes for society.

SC: And now I am speaking to you in your greenhouse. How did that project evolve from your activism?

DTs: I started last spring when we gathered seedlings from the park. I decided to replace an old garage with a greenhouse so I crowd-funded the project. In September, we demolished the garage. We then received funding from Orbeliani Georgia, USAID, and HEKS/EPER. We built the greenhouse, presentation, yoga space, outdoor toilet, and paths. My focus now is on this urban garden space. The funny thing is I am not the guy who knows all the names of the plants: this is more of a social space where we spread the word about the situation in Rustavi. Of course, we are talking about global environmental problems, but we center discussions in Rustavi.

SC: Tell us about growing up in Rustavi.

DTs: I grew up in the house where I built the garden, with my four brothers. I am the youngest. I have some mixed feelings about this city. Sometimes I want to blow it all away, yet I am attached to it. When I was 16, a group of my friends wanted to do a reforestation project, but we were too young and inexperienced. From a young age, I wanted to do some good for this city. I always think I want to leave here, yet I can’t.

KC: Can you give us some background on Rustavi?

Dts: Rustavi was built as an industrial city, but most of them closed after the fall of the Soviet Union. Many residents don’t know that 45 factories are still operating, and about 23 of those have emissions that cause air pollution. We have a fertilizer plant, Rustavi Azot, and Heidelberg Cement. Heidelberg was one of the worst, but they added filters. Now, some factories have filters, but some don’t use them. When we started our work, they had no chimneys or cooling systems. Now, because of our work, they have them. I can’t believe that happened. A lot of the credit goes to Tina Maghedani—she continues this work.

SC: You’re running a lot of youth programs at the garden.

DTs: We are working with school programs. They learn about plants and soils. We mix soil, and plant seedlings and use the microscope. A few years ago, out of 30 schools, we approached to ask them to visit, but only one replied. Most people my age and older don’t have time to concentrate on this kind of work. If we focus on this generation of young people, we can create a healthier community in Rustavi.

SC: What other programs do you want to develop at the Garden?

DTs: I want to create a year-round cycle of programs. We have music events, screenings, and a bar. I want to involve more professionals, so I can focus on my professional work as a cameraman. I want this to be a space for screening Georgian documentary films.

SC: When you look at the history of Rustavi, there were so many social and cultural spaces for the workers. After privatization, nothing replaced those spaces.

DTs This is the first semi-public space about air pollution and the environment. When the students come, I teach them about the air quality portal. We talk about air pollution: breathing comes first. Then they learn about composting and recycling. We have a recycling plant in Rustavi.

SC: I wonder what it is like to be a teenager in Rustavi today, knowing everything was organized and built–railroads, plants, housing–around a system that no longer exists. What year were you born?

Dts: I was born in 1993. If I was born a year earlier I would be different. [Georgia became an independent nation again in 1991]. We didn’t have consistent electricity until 2003.

SC: What else has changed in the environment since then?

Dts: About 20 years ago, there was a forest along the Mtkvari River, with wildlife–about 200 hectares. My father said he used to go there and hunt rabbits. Today there are about six trees left. The land is used for pasture, and no new trees can grow. I want to buy or rent this territory from the city for a symbolic price to regenerate this forest. We plan a campaign around the hashtag #growyourownforest.

Other projects involve waste management in the city and cleaning up the river. I want to get this inflatable boom to collect the plastic bottles that gather in the river in the spring. But sometimes it is difficult to get people to care: they will say:: “it used to be so much worse.

KC: How do you get people to care about air pollution-especially when it is something you can’t see?

Dts: In the Soviet era the air pollution was part of the identity of the city. You can see the pollution in short film “Tuzhi/თუჯი” (also known as La Fonte, or Cast Iron, 1964) by director Otar Ioseliani. It depicts daily life in the Rustavi metallurgical plant.

One of the funniest things that happened recently to change the situation was the Deputy Environmental Minister said that when PM10 and PM2.5 are higher than 150 and PM 2.5 is higher than 75 is deadly. And she said: “In that case, the population of Rustavi needs to stay home and wear masks.” I thought she would get crushed or fired for that. But after she said that, the government’s language changed, and things started to improve. And both parties talk about improving the air quality now, during election times. So things are better, but sometimes we get “trans-border pollution from Africa or Iraq. You can track that type of pollution with the EU’s Copernicus site.

Then the government officials started going to the factories, shooting videos that showed the scale of the problem, saying that something must be done. They started planting trees. It was funny to see them doing these activities.

SC: You’ve been attending climate conferences recently. What is happening there?

DTs: In Budapest, I attended the Youth in Climate Summit. There we discussed international environmental law and learned how to sue the state or the private sector and force them into compliance. I met many people there, and now we have a handbook of tactics to help build environmental law cases.

KC: What else are you working on?

DTs: I am planning a project to replant the forest along the Mtkvari river floodplain in Rustavi. I want to start connecting our initiatives, including expanding our space in the city.

SC: Thank you, Data. We look forward to seeing what evolves in Rustavi.