Uncovering the Hidden Rivers of Tbilisi

An interview with Timothy Merkel, author of the Instagram documentary project @riversoftbilisi

The Instagram account @Riversoftbilisi gathers scenes of rushing water hemmed by concrete, crumbling infrastructure, and dense thickets and wetlands. The work of writer and musician Timothy Merkel, the account details the undisturbed reaches of the city’s urban waterways. His techniques of exploration and documentation recall those outlined in Sean Burkholder and Karen Lutsky’s essay “Curious Methods.” Burkholder and Lutsky encourage people “to recover the value in open-ended, ground-level exploration, or what we call curious methods… not to extract meaning, but to ask questions, to probe the environment.”

At the same time, Merkel’s project exemplifies a practice of Landscape Citizenship, described by landscape theorist Tim Waterman as “active processes of affinity, experience, and applied landscape knowledge and interactions.”1 Merkel’s Instagram stories make forgotten lands public through description and documentation. The project exposes the uneasy interfaces between the city’s urban and natural systems and the potential of treating these networks and edges with care. The result is a practice of “place-making” through interpretation that saves a generous portion of inscrutability to our desires and imaginings of what the city was, and what it can be.

I interviewed Merkel this fall to learn more about this ongoing project.

[For more information about the city’s watercourses and flood risks, see the documents "Hazards of Disastrous Flooding in the City of Tbilisi" and the UNDP Flood Assessment: Tbilisi]

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

SC: What first caught your attention about the rivers of Tbilisi and why did you start this project?

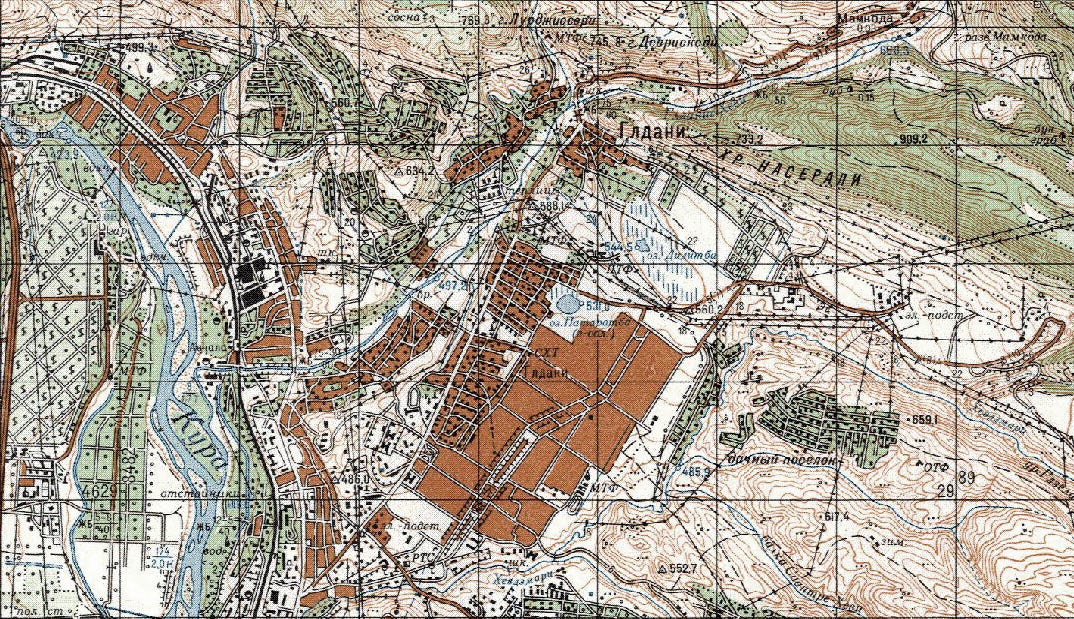

TM: I am fascinated by geography and often spend time looking over maps, trying to coordinate the understanding of my eyes with structural representations, to see around corners and follow where things go. Tbilisi is such a spectacular natural setting for a city. Sometimes I have tried to imagine the hills and valleys without any development up until the last century, perhaps dotted with small villages and settlements.

“[In Tbilisi] We constantly have to ascend, descend, go around, and navigate the traces of these rivers.”

Tbilisi is constructed in a river valley, defined by the Mtkvari River. Neighborhoods are separated by canyons, formerly the beds of rivers which now run in pipes underground. We constantly have to ascend, descend, go around, and navigate the traces of these rivers.

SC: Yes! In Tbilisi you have to twine your way from canyons to plateaus.

TM: Starting in the late 19th century, Tbilisi’s rivers were hidden, buried, built walls, drained, and diverted and drained to support urban development. Today’s construction compounds the impacts on rivers to dangerous levels. The flooding of the Vere in 2015 was a dramatic event demonstrating the power of the river. The flood led me to question where the waters come from, where they go, and how they are manipulated.

In 2020 I began documenting a section of the Rioni valley in west Georgia. At the time, activists were protesting the planned Namakhvani hydropower project on the Rioni River over safety and ecological concerns (the HPP project has since been canceled). “Rivers of Tbilisi” emerged as a catalog of significant rivers of Tbilisi and their history and hydrology. I posted this work to a Telegram group focused on archaeological sites in Dighomi. That caught people’s attention, so I started the Instagram page with an expedition to the Vere River’s tributaries in Saburtalo.

SC: Can you tell us about yourself and how you ended up in Georgia?

TM: I’m an American, but Georgia is my home now. I first came in 2009 with some Georgian classmates for a summer philosophy seminar in Tbilisi, and two years later began teaching English in rural Georgian schools. I learned Georgian and fell deeply in love with the place and people. I continued traveling and studying in Europe, but Georgia was where I felt happy and free.

In 2019 I hiked for two months from Mtskheta to the Black Sea, via a remote and circuitous route. I do freelance work for a living, and dedicate my time to music, poetry, exploration, and activism.

SC: Why did you choose Instagram as a platform for the project?

TM: At first, I did not know how to organize the information I was sharing. I began by posting stories live from the locations directly from my account and sharing pictures with a Telegram group. To make the work accessible and organized I started a dedicated account on Instagram.

SC: You primarily use the Instagram Stories feature. What are its advantages?

The vertical image format is suitable for framing the narrow valleys of Tbilisi’s tributaries, and it is easy to caption and group images. The statistics show that most people do not watch the whole story when they are up, so I archive the stories on my profile page.

Someday I may translate the work to a platform like a website or physical exhibition. But for now, the freedom and informality of Instagram suit the spirit of the project.

SC: Your stories are fresh and honest. In our field, we often overthink documentation, and it loses potency.

SC: Since initiating this work, have your impressions or focus changed? Has the act of exploring and documenting made you think about future projects?

My explorations have revealed the limits of my ecological knowledge. How do rivers interact with underlying rocks and soils to create a valley, how do water tables work, and what causes intermittency in a stream? I started this project almost on a whim, but I feel an increasing sense of commitment over time. It resonates with people and their enthusiasm and interest motivate me.

Ecological questions don't receive a lot of attention in Georgia. I hope this project attunes people to the processes that are beneath their feet.

SC: That social connection is critical. I first saw your posts about the activities around Lado’s Garden, which has a community of people that want to make it a public space. There’s a sense of disempowerment about ecological issues in the city. The interface between the mountains and the city is often uninviting dumping grounds. Your project breaks through those barriers and connects people to these landscapes, and encourages exploration.

TM: Ecological questions do not receive a lot of attention in Georgia. I hope this project attunes people to the processes that are beneath their feet.

I plan to document all neighborhoods and major valleys of Tbilisi. Every exploration leaves me with an expanded sense of the scale and complexity of Tbilisi's hydrology, and this motivates me to continue.

SC: Tell us about the paper cranes: the Oritsuru that you place in the waterways.

At the beginning of the project, I left folded paper cranes in several rivers as a kind of private performance or prayer for ecological balance and healing.

I am experimenting with other ways of capturing moments of the rivers with field recordings. I am considering collecting artifacts from expeditions. The project will continue to evolve over the next few years.

SC: Your photos often reveal the whole area like the canyon, and the context, but also small details like dams and pipes, and include annotations. What are you trying to communicate by shifting the scale of the frame and/or subject?

The environment is made up of a huge constellation of details. In the urban context, pipes are the default means of interface with a river, as they divert water for development. As such, I focus on the places where a river disappears or emerges from pipes.

SC: Yes. Especially with increased developmental and impermeable areas, stormwater volumes and speeds increase, and pipe and culvert dimensions are no longer sufficient to handle the flows. And we lose the complexity of riparian environments and the biodiversity they support.

TM: We lose the complex interactions of the river with the soil, the banks, the weather, and the species that inhabit it. The ecosystem services and public spaces these rivers provide are ignored in favor of construction. We could reconsider Tbilisi’s rivers as a network of linear wildlands that can improve city life, rather than an obstacle to development.

We could reconsider Tbilisi’s rivers as a network of linear wildlands that can improve city life, rather than an obstacle to development.

SC: Indeed, many tributaries and riverbanks of the city could be cleaned up and retrofitted with paths and access points, like the work underway in Toronto’s ravines.

SC: Where do you find additional information about the rivers? Are there any sources or resources you want but cannot access?

Sometimes it comes from anecdotes or articles. Sometimes I do more research after making a discovery. I am even more attuned to information about rivers and want to increase my knowledge of urban hydrology.

A helpful resource is Nino Gventsadze’s thesis on Tbilisi’s rivers. I am curious about the vast system diverted from the Iori River that fills the Tbilisi Sea. (see Jesse Vogler’s work on the Tbilisi Sea and the Meurneoba)

SC: Many large-scale landscape rehabilitation projects began because a small group of people had a vision to improve the built environment. These include groups like Friends of The High Line, and Friends of the Los Angeles River, among others. Do you see this project as a means to start a larger movement?

I hope so! The urban ecology of Tbilisi is approaching a kind of catastrophic state. I do not think the environmental laws are sufficient or enforced. Citizens are ready for change. I welcome any other observers, adventurers, and explorers—and hope for the day when planners and developers take the rivers into account.

SC: Yes—the mayor has rehabilitated parks and it’s a huge improvement, but these are largely static projects by architects, without intelligent integration of hydrology.

SC What rivers are next on your list?

I recently documented the Gldaniskhvei river, and next is the Dighomi River, starting at its headwaters near Beverti Village. My list includes Lisi Lake, a return to Gldani, and the waterfall on the cliffs above the Right Bank highway.

What has been the biggest surprise in this project? What assumptions did it challenge?

I am surprised how the scope of the project has grown. Now I am attuned to the ways water reveals ways of living, the sites of speed and stagnancy, cleanliness and filth. Rivers are symbols of great power; they relate to us on an elemental, even personal level. That people are interested in these stories is a testimony of the power of rivers and how each one of us can connect to them.

Interested in joining Timothy on his next expedition? DM him via the Rivers of Tbilisi account.

#newcaucasusgardens, #riversofgeorgia

Tim Waterman, Jane Wolff, and Ed Wall, “Landscape Citizenships,” in Landscape Citizenships (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2021), p. 2.