Matt Dallos’ Thicket Workshop “merges design and research to create plant-focused, ecological public and private landscapes.” In this interview, we discuss how his practice grew from the “intellectual surplus” of landscape history studies at Cornell University and his training as a landscape architect at Penn State.

Your PhD work is on the history of wildness in American culture, particularly with engaging wildness “close-to-home in the garden” and how there were hints of design and ecology in the late 19th and early 20th century. Can you offer more insight into this?

Interest in encouraging wildness in the garden can today appear very contemporary, but I’ve come to appreciate its deeper history better.

There’s this moment in the 1880s through the 1910s or so when, in the U.S. at least, divisions between what was considered nature and culture, between wild and cultivated, were more flexible, contested, and not as delineated as they would prove to be for much of the twentieth century. There’s an interest in cultivating wildness close to home in the United States.

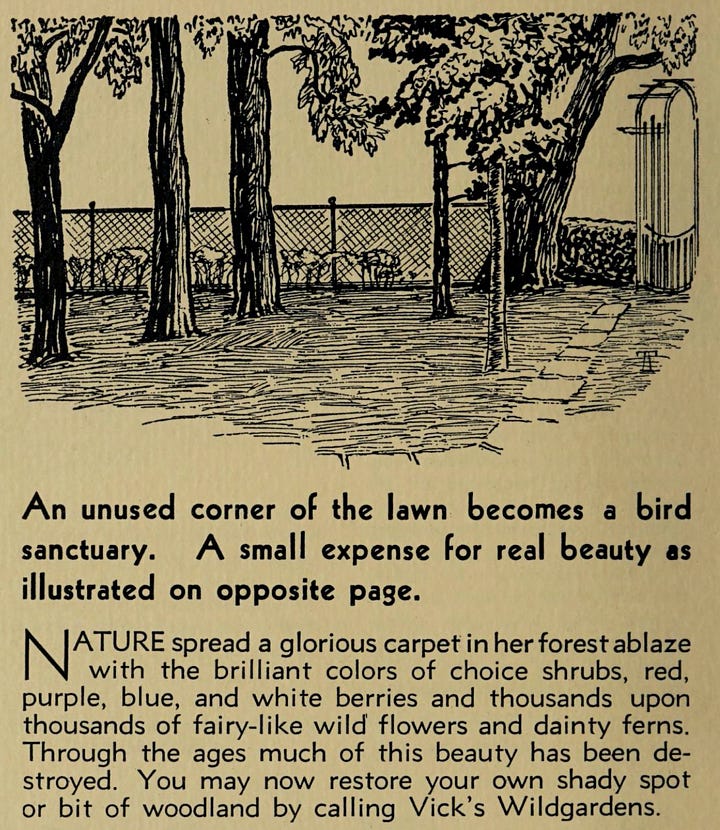

Wild gardens have been discussed and debated in the United States at least since William Robinson published The Wild Garden in 1870. It’s really after the turn of the century when the idea gains traction. What follows is a few decades when early ecological ideas overlapped with a socially rooted and non-expert-driven interest in cultivating close-to-home wildness.

There’s this moment in the 1880s through the 1910s or so when, in the U.S. at least, divisions between what was considered nature and culture, between wild and cultivated, were more flexible, contested, and not as delineated as they would prove to be for much of the twentieth century.

It’s a time when individuals were calling for the creation of national wild gardening clubs, when individuals were gathering local community members and starting public wild gardens as a way to build community, when schoolchildren spent time in wild gardens as part of their standard curriculum. It was also about escaping the pollution and disruption of modernity and tangled up in the history of suburbanization.

By the 1930s, this moment was largely gone, and it really wouldn’t return as a viable line of environmental thought until the 1980s and 1990s.

Are there aspects of those perspectives that we can see in today’s “wild gardening” approaches?

Other than the fact that any pursuit of wildness is deeply rooted in European scenic ideals, I don’t think there’s much direct intellectual connection between today’s wild gardens and those from the turn of the twentieth century.

There was this divide in the mid-twentieth century when the type of environmental thought upon which wild gardens relied wasn’t tenable. That meant many of the ideas didn’t persist. (There are exceptions. I see designer Darrell Morrison’s late-1960s interest in American Plants for American Gardens as one example. But even he notes in his book Beauty of the Wild that this connection was disjointed.)

In more ways than we might care to admit, the current dialog surrounding wild gardens or naturalistic planting—whatever you might now call it—is still catching up. That earlier iteration of wild gardens raised complex questions about building community, the relationship between art and ecology, and initiating a human culture of wild gardening. We’re just now returning to some of these concepts in many ways.

Of course, there are incidental overlaps in formal questions between then and now. Wild gardeners in that earlier moment also questioned how plants should be arranged to create a certain human experience of wildness or match a particular distribution found in a natural plant community. They even looked to spontaneous plant communities, such as remnant prairies along railroads,

to inform plantings.

What historical landscape works did you study that have informed your current practice?

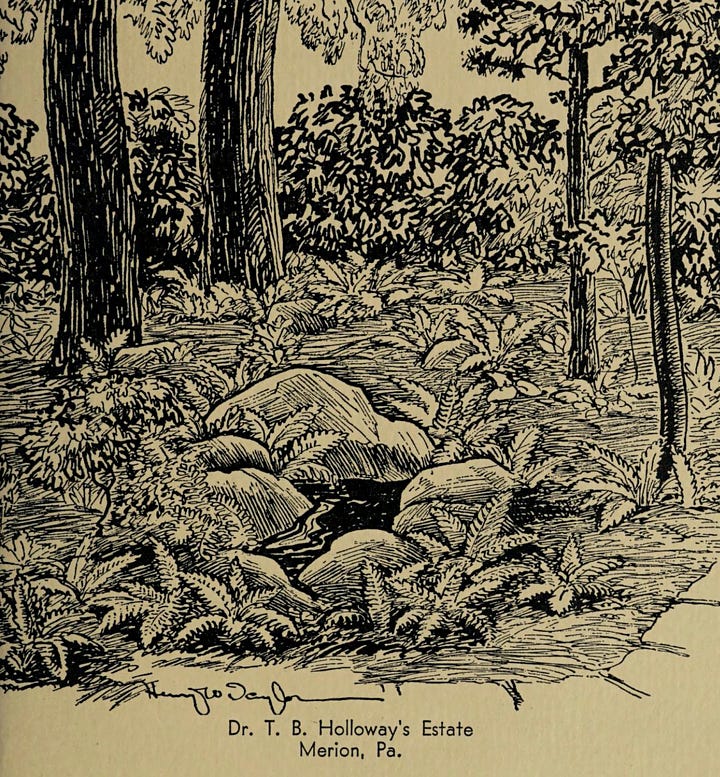

One is a wild garden in a quarry designed by Warren Manning outside of Philadelphia, on an estate called Dolobran in the late 1890s. It is prominent in the archives because there are photographs of it and articles that describe it and discuss some of the planting practices that helped to manage it. It’s also a stunning site in an abandoned quarry, which very much fits with what Manning thought a wild garden should be—that it was appropriate when the setting was rugged, varied, broken: picturesque. But it’s wild gardens that exist slightly outside of the landscape architectural canon that I think have the most to offer us today.

In Minneapolis, a wild garden was started in 1907 by a group of teachers. Built adjacent to the city and surrounded by land that was developed or would be developed as housing, the garden was a few acres at first but would expand to more than 25. It was managed by a retired school teacher, Eloise Butler, for over twenty years. With volunteers, Butler guided the development of plant communities, introduced many species to the site, and maintained a trail network.

What’s so fascinating about it is how the garden insinuated itself into local society. Approaching a century after the death of Butler, it’s still there and apparently thriving. It is a lesson to all designers about what makes a project durable! There’s still an active group involved in the site, and the garden has a web presence. The garden is still alive and dynamic, even if the language is now more about preservation than gardening.

In rural Connecticut near the turn of the 20th century, Benjamin Thomas Fairchild, the owner of a chemical company, bought an abandoned farm and then spent many years turning it into a cross between an ecological restoration project and a wild garden. I find it to be a surprisingly contemporary project. He spent much of his effort experimenting with planting strategies and management strategies to create desired plant communities or certain experiences for people on the site. Unfortunately, it’s not that well documented. It’s still there, though today it’s a protected nature preserve, not a garden.

And then there were many wild gardens, in front yards, for example, that were built in cities across the United States in the 1910s and 1920s. There’s almost no documentation of them. But it’s exciting to think that, for example, a woman living in rural Nebraska wanted to plant a garden of local prairie species in her yard in the early years of the 20th century—and that she wrote about it and shared her ideas and used it as a nexus to gather a community of like-minded people. I’m sure many other stories like that are buried in the archives.

How did the Thicket Workshop emerge from the more academic/research aspects of your work?

When I was well into my PhD, my research showed how environmental politics, culture, and plant practices have been historically intertwined. That research made me want to work in design in a way that could bring together plant-centric research, practice, and an almost manifesto-based approach. How could I use built works to contribute to this critical dialog of plants and culture?

It’s been a somewhat difficult position to explain to my humanities colleagues. They often see my so-called applied interests in design as disjointed from my scholarly interests. I don’t see it that way at all. To me, they are inseparable—and that’s really what I want them to be. It makes me a better teacher, a better researcher, and a better designer. Digging in the archives, reading environmental humanities theory, and knowing the root structure of wild ginger are examples of the various modes I strive to bring together. There’s a path forward through it all, I swear.

Thrift is a drive in your work, in the locations and materials, and like all good design processes with limits and improvisation on site, it recombines into something complex with a new set of aesthetic rules to play with. What are some of those themes?

Maybe it’s worthwhile to start with the source of the thrift. In many cases, it’s imposed: a client has a small budget yet desires to make changes to their property. In other cases, it’s my argument: a client might have a sufficient budget, but the scale or condition of the property demands a multi-year intervention rather than a one-off planting. In small, experimental public projects, I often propose the work, and thus, there’s no budget, so I’m scrounging for everything.

I see planting as a much more responsive and adaptable set of land practices. It’s great if there’s a budget to search widely for specific species of native or near-native plants and a budget to plant 50 shrubs. But what if a client wants to make their 3-acre property more beneficial for invertebrates but has a small budget and the property is a thicket of invasive buckthorn? As designers what do we do then? Where is the line between ecological restoration and design? Does it matter?

Of the themes this has led me to, I’d say an embrace of imperfection has been the most common. I used to think of planting as something that had to meet predetermined ideals. We all get drawn in by those glossy images in monographs. I see planting as a much more responsive and adaptable set of land practices. It’s great if there’s a budget to search widely for specific species of native or near-native plants and a budget to plant 50 shrubs. But what if a client wants to make their 3-acre property more beneficial for invertebrates but has a small budget and the property is a thicket of invasive buckthorn? As designers, what do we do then? Where is the line between ecological restoration and design? Does it matter?

Embracing imperfection often means living with non-native grasses as a matrix between otherwise native plants; sometimes, it means the only gardening tool is a lawn mower that the client borrows from a friend once per month; sometimes, it means refereeing spontaneous plants toward desired effects. I’ve found this type of work to be incredibly difficult to photograph so far. But it seems worthwhile. In an expanded field, so to say, of planting design, these have to be situations with which we’re willing to engage.

I’m also very interested in working with clients who want to do some of the work themselves. Is the client hoping to engage directly with the site management? Or learn? Are they willing to grow plants? Will they hack down Rosa multiflora on the weekends?

And there are benefits beyond thrift in that approach: a client engaged with the work, I believe, is much more likely to stick with the project; is much more likely to see their view of the world and their environmental politics skewed a bit by that engagement; is much more likely to become an advocate to their friends and family.

As ecological restoration (as applied ecology) gained momentum in the 60s-70s, you mentioned that environmentalists were nervous that the practice would justify greater exploitation. In restoration, the naturalization aesthetic is baked in. Do you see any means or theorists who challenge that approach, to make meaning and develop new practices? (Natasha Myers)

More generally, I think much environmental thought in the twentieth century in the United States held a fair amount of anxiety about human intervention in the natural world. Whether you link this to the rise of the wilderness ethos or to some long-term trend toward viewing Nature as an inherently balanced entity in the absence of humans, it crimped environmental thought and politics for much of the century. We’re still living with the legacy of this in many ways.

I do think there has been a challenge to this mindset over the past few decades. Some of the work of William Jordan in ecological restoration in the early 2000s made the case for the deeply cultural aspects of restoration work, which to me suggests an environmental politics that’s very hopeful.

More recently, I’ve found the work of some ecofeminists and scholars in plant humanities, making me think about the role of plants in our built environment. Natasha Myers' work has been particularly helpful. And I’d recommend the work of Colette Palamar to anyone, especially the article “Restorashyn: Ecofeminist Restoration.” Both of these make me think about how to respond to an invasive buckthorn thicket.

How is 2024 looking for you on these plots?

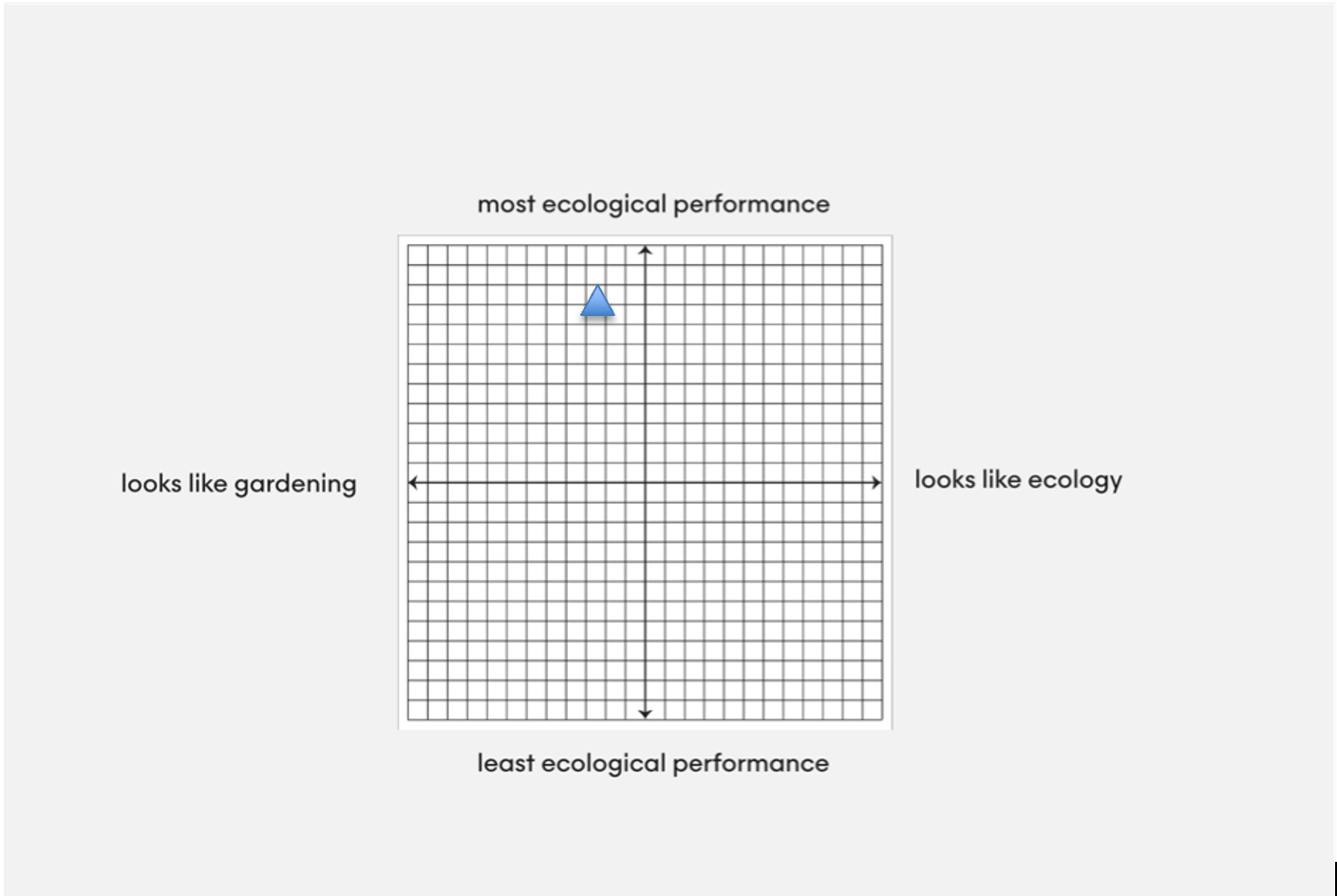

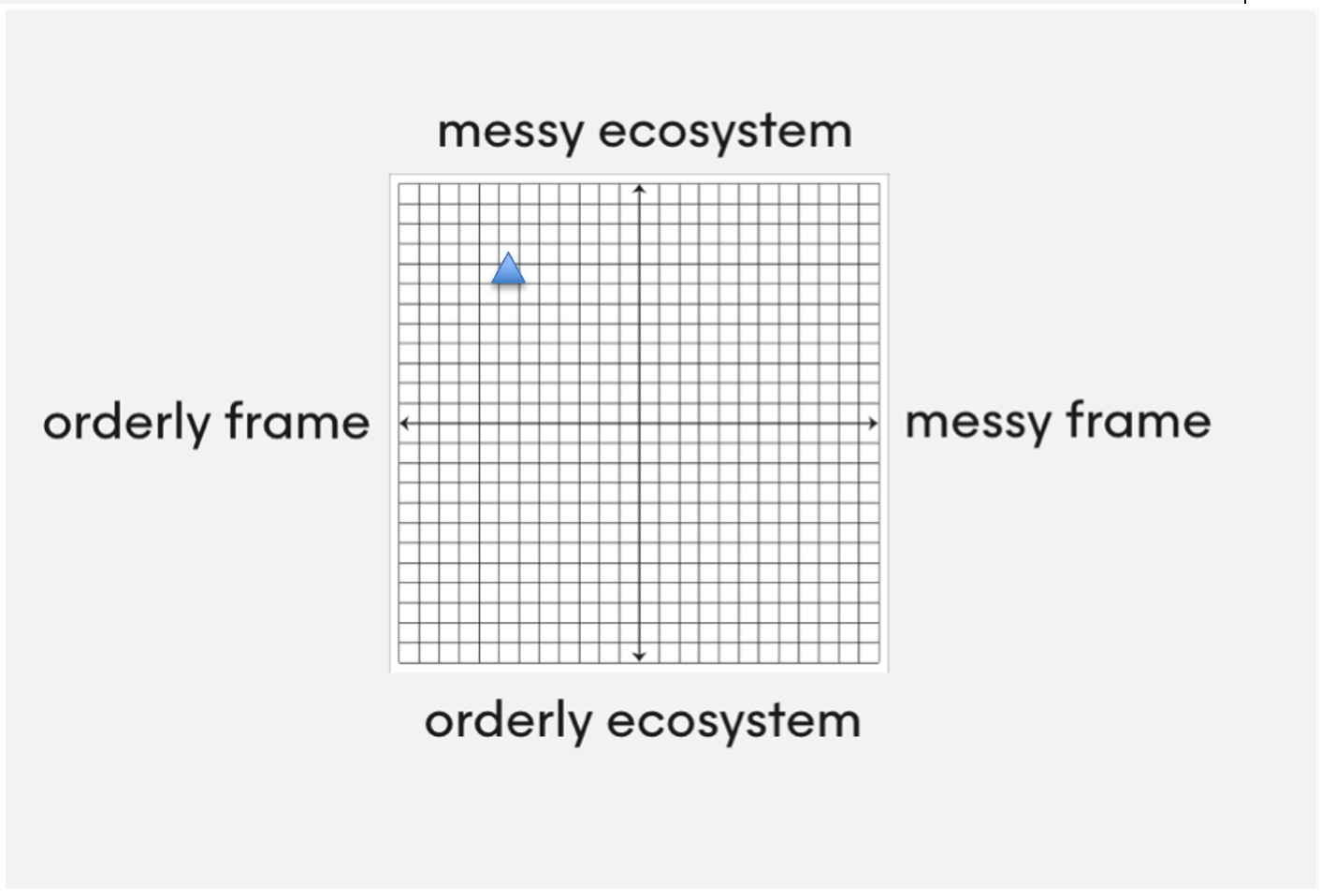

Responsive! Especially to client goals, as the questions implied here tend to come up in conversations with clients. I might also ask for a z-axis here to represent time. There might be some really informative arcs to draw in that model. But if I’m putting a single point, then it’s:

You’re curious for designers to provide more honest exposition on the design process- you speak of the overlap between the personal essay and the design process.

I’m fascinated by the possibilities of the personal essay to offer more insightful takes on what it means to design, tend, and live with designed landscapes, especially those that thoughtfully involve plants.

Designers—write about your work on the process! First, I find these essays incredibly valuable as a designer, just to get a sense of what other designers are thinking and doing. Second, as an historian, I’ve come to realize how quickly the ideas behind a project fade. Lately I’ve been writing about some 1970s and 1980s plant practices on vacant lots, and I’m necessarily piecing together this story from fragments of news articles. What I wouldn’t give to have a narrative account of one of these projects!

Social media, in many ways, seems to offer some of these more off-the-cuff remarks on projects and inspiration. I think that’s what keeps me coming back to Instagram.

There are many examples of designers/plant people already adopting a more personal and essayistic approach to sharing insights. Here are a few:

“Improvised Landscapes” Nicholas Anderson

“Curious Methods” Karen Lutsky and Sean Burkholder

30 Trees: And Why Landscape Architects Love Them

In many ways, writings such as these are pushing back against efforts of scientification or rationalization efforts of the design fields that have been in motion for so long.

You mentioned that planting design needs a critical overhaul in the BSLA/MLA curriculum. What are some areas where there could be more rigor?

In my experience, planting design often gets lumped in with the technical classes mandated by accreditation. (There are exceptions, of course!) That means the class ends up being about more technical details: about the correct way to group plants, about plant spacing, about proper plant communities for a region, or about identifying a certain accepted set of species familiar in horticulture.

I want students to plant seeds and watch them grow. I want them to understand the effort required to plant a flat of 50 plugs with an electric auger. But I also want them to spend time thinking like a lichen. I want them to think broadly and radically about how planting design can be related to plant preservation, culture, and regional economies.

It’s about practices that meet established expectations. However, I firmly believe that we need more challenging and rigorous questions that inform how and why we teach planting design.That question is: How can I spark an enduring and critical intellectual and material curiosity about the design possibilities of plants?

I want planting design courses that embrace both materials and ideas. I want students to plant seeds and watch them grow. I want them to understand the effort required to plant a flat of 50 plugs with an electric auger. But I also want them to spend time thinking like a lichen. I want them to think broadly and radically about how planting design can be related to plant preservation, culture, and regional economies. I find the juxtaposition of these methodologies, epistemologies, and practices necessary.

Often, planting design courses are too focused on teaching planting as a technical skill that follows a conventional route to solve problems using rational, textbook methods. I want to give students the tools, theories, and space to pursue new questions, practices, and arguments.

Merging the material and the intellectual, planting design has radical ecological and cultural potential in landscape design. That framing offers much potential as to how we teach plants.

Thank you Matt for speaking with us. You can follow Matt Dallos and Thicket Workshop on Instagram.