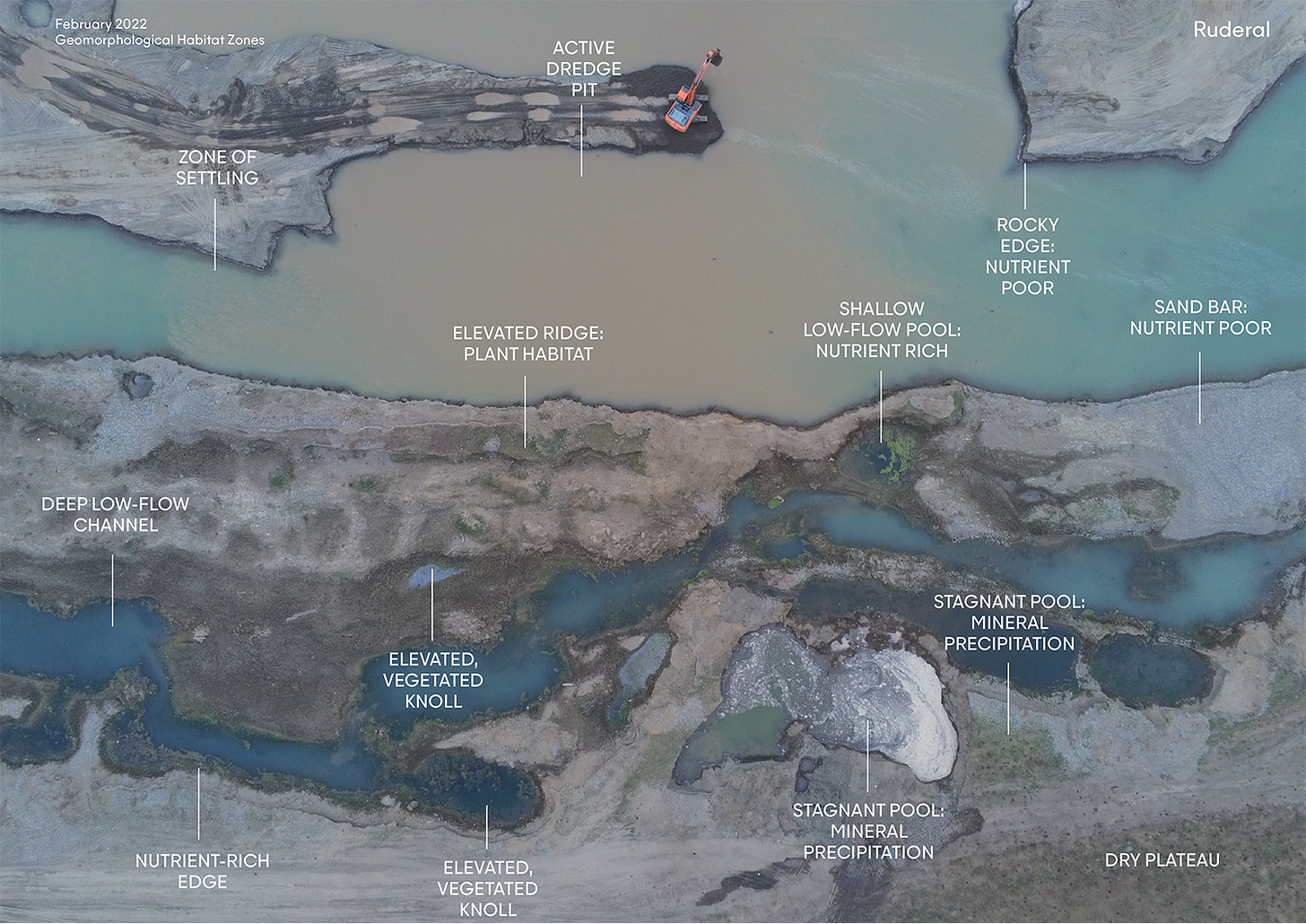

After our initial visit in late winter, students from VAADs at the Free University worked with the Ruderal team to compile satellite imagery, reviewed drone footage, and composed diagrams describing the mining process and its extents.

While the drone footage from the February visit shows a sparse winter landscape, the satellite imagery shows a river in constant flux, coming to life each spring as a new layer of vegetation spreads over the bed of silt and rocks freshly deposited by winter flooding. As spring progresses, birds, mammals, and amphibians move in to establish a new, temporary ecosystem. This partial record of the last decade reveals the impact of mining activities on the riverbed over time. Ballast mining disturbs the riverbed on a timeline of weeks to months, but this impact can be superseded by spring floods that occur on a much larger scale.

Excavators grapple with this shifting landscape by creating dambas, (roughly translated as “dam”), which allow them to direct the river and its powerful floods. According to the on-site excavators, dambas can be built to protect machinery, but they can also be removed to allow larger floods to replenish excavated material.

Riverbed ecosystems are driven by disturbance rather than stability, which complicates traditional notions of ecological restoration within these systems. Further complicating matters his quarry is an active mine: mining activity will continue throughout the implementation of the proposed project. In response to these conditions, we suggest that mining and damba building processes can be harnessed to increased the geomorphological diversity of the mining site. Processes of excavation, damba building, and periodic flooding have the potential to create a wide range of microhabitats that support increased species biodiversity.

In the next steps of our project, we will observe sites with distinct morphological conditions within this landscape of uneven disturbance to document how spring and summer bring these remarkable microhabitats to life.