Periodically we will draw work from our archives—texts, drawings, criticism, coursework, and projects—to provide background on the studio's foundations and our current work. This month we’re sharing the chapter “Bigger MPs”, originally published in Representing Landscapes: Hybrid” by Nadia Amoroso (Routledge, 2015), edited for the web. Hybrid methods of landscape representation can unite the precision and reproducibility of digital tools with the inflection and invention of handicraft. In a typical analog-to-digital workflow, hand-drawn landscape sketches are refined using any number of applications and fabrication devices. Re-mixing this (now) traditional workflow offers possibilities for innovation in hybrid landscape representation.

With digital fabrication workflows and products, we can make tools and armatures for use with other media. Examples include creating a CAD milled surface for sand casting glass tiles; making 3D printed armatures as a frame for fiberglass application; or milling or laser-cutting plates for printmaking.

In 2104, at Knowlton School at The Ohio State University, I teamed with Nick Glase to lead a design and planning studio on the 550- square mile Big Darby Creek watershed in central Ohio. Titled Bigger Darby, the work was exhibited in the Banvard Gallery at Knowlton School and won an ASLA Student Honor Award.

In landscape planning studios participants study land-use conflicts; determine ecological assets and vulnerabilities; study past and forecast future development patterns, and perform visual landscape analysis to determine landscape character. Study areas are defined by watershed boundaries, shared material, economic, or ecological concerns. Planning studio participants manipulate landscape data in the coarse-scale of GIS polygons and propose design alternatives. However, the design of elements that enhance landscape character is often left to “others” to work at smaller scales, such as the subdivision, schoolyard, infiltration basin, streetscape, or infrastructural corridor.

During the planning and analysis phase of the studio, we asked participants to consider how watershed improvement goals can be met by enhancing the landscape identity of the region. In other words, can we start small to work big? For the exhibition, participants were tasked with making a cohesive group of hybrid models and drawings, using digital fabrication tools to make tools for representation.

In my research and teaching, I examine how smaller-scale landscape interventions—from the hedgerow to the ditch—can enhance both ecological function and landscape identity. In studios, we look at the ways ecological, cultural, political, atmospheric, and geological factors contribute to material landscape identity, and how landscape identity is reiterated through representational modes.

WATERSHED PLANNING AND LANDSCAPE IDENTITY

Watershed planning addresses environmental issues such as flooding, habitat degradation, and water quality. In recent decades, more regions and municipalities are adopting watershed-planning models to shape development and environmental goals, like the Rapid 5 project underway in Columbus, Unfortunately, most watershed planning work is policy-based and not immediately visible in the landscape. To increase the visibility of the landscape identity in the Bigger Darby watershed, we asked participants to consider:

How can small-scale interventions aggregate into coherence at the scale of the landscape?

Can these small-scale interventions enhance landscape identity and lead to greater public support and participation in watershed protection efforts?

ABOUT THE SITE: THE BIG DARBY CREEK WATERSHED

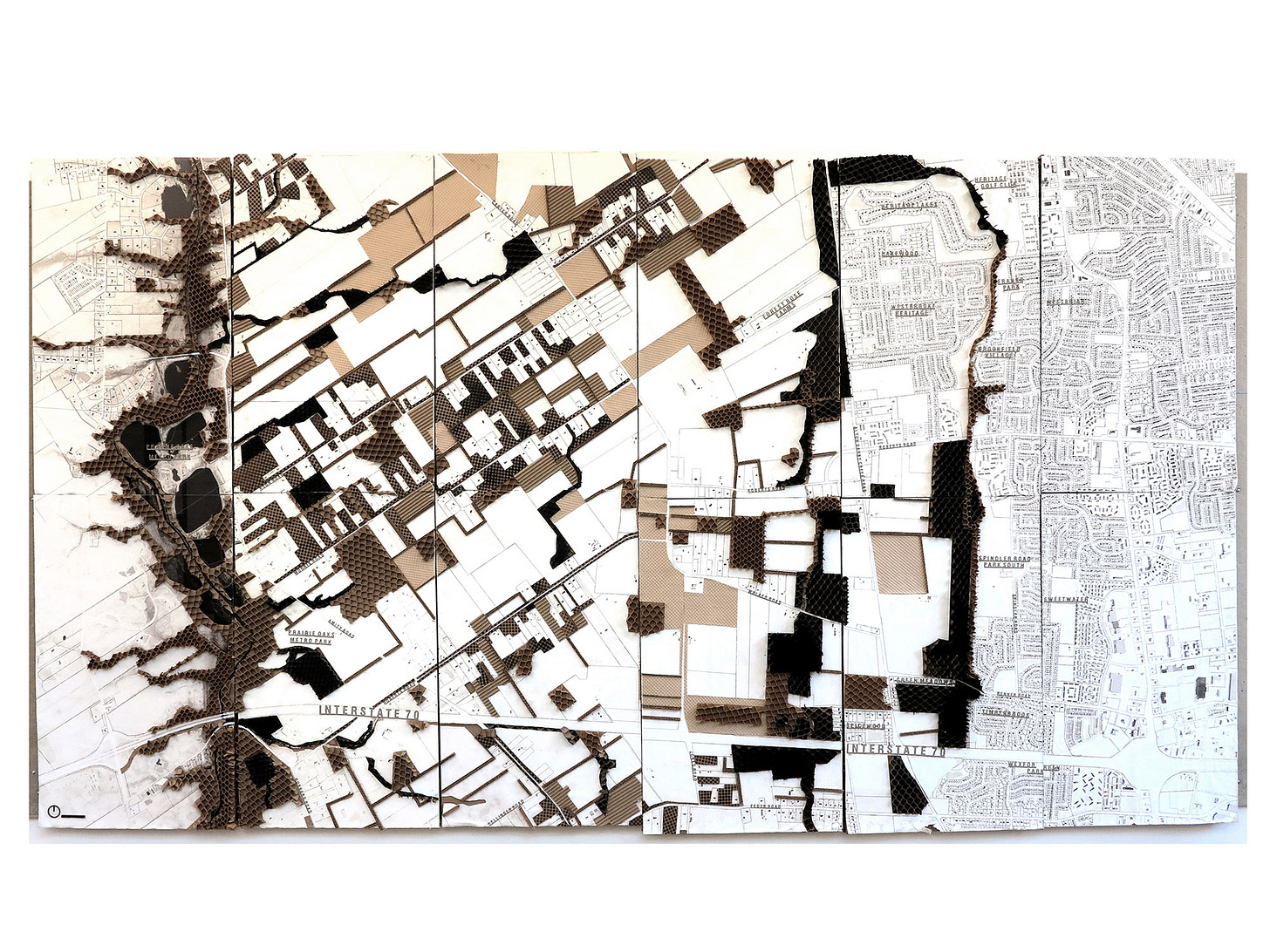

Near downtown Columbus Ohio, the Big Darby Creek Watershed area is one of the most diverse ecosystems in the Midwest. The river is a tributary of the Scioto River which flows into the Missouri-Ohio-Mississippi basin. The riparian zone of the creek is home to 38 endangered species. Here the western suburbs of Columbus interface with the dominant agriculture of western Ohio. Landscape structure in the region is defined by the parcels of the Virginia Military Grid (skewed relative to the orthogonal Jeffersonian Grid), the landscape is a rich patchwork of typologies including farmland, riparian corridors, wetlands, woodlots, old fields, restored prairie, savannah, strip development, cluster development, and single-family subdivisions. Key characteristics of lands within the watershed are robust riparian edges, open areas of farmland defined by hedgerows, ditches, and field lines, and ‘islands’ of recent development: single-family homes on large lots, or cul-de-sac clusters—in former agricultural fields.

Big and Little Darby Creeks are protected under State and National Scenic Rivers designations. These protections limit new development within the region. In 2006, EDAW published the Big Darby Accord Watershed Master Plan (BDAWMP). The plan allowed for development while protecting the watershed from agricultural and suburban water pollution. As typical of most watershed master plans, the BDAWMP advocated for tiered conservation strategies, acquisition of sensitive areas, enhancement of ecological zones, and introduced a tool kit of standard Best Management Practices, or BMPs such as grassed waterways, riparian setbacks, and stormwater infiltration basins. In this plan, the success of the big—the tiered zones of conservation—is tied to the small in the form of a variety of BMPs.

Now in its 8th year, the BDAWMP is progressive in its intentions and successful in practice; however, generic suburban development patterns are eroding the landscape character of the region, and support for the BDAWMP is waning. We reviewed the BDAWMP and noted that the plan overlooks the site’s rich matrix of middle-scale land-use patterns in favor of ‘coarse’ grain habitat corridors. From this analysis, we proposed a hypothesis: could we improve civic support for the BDAWMP by strengthening the visual coherence of the landscape?

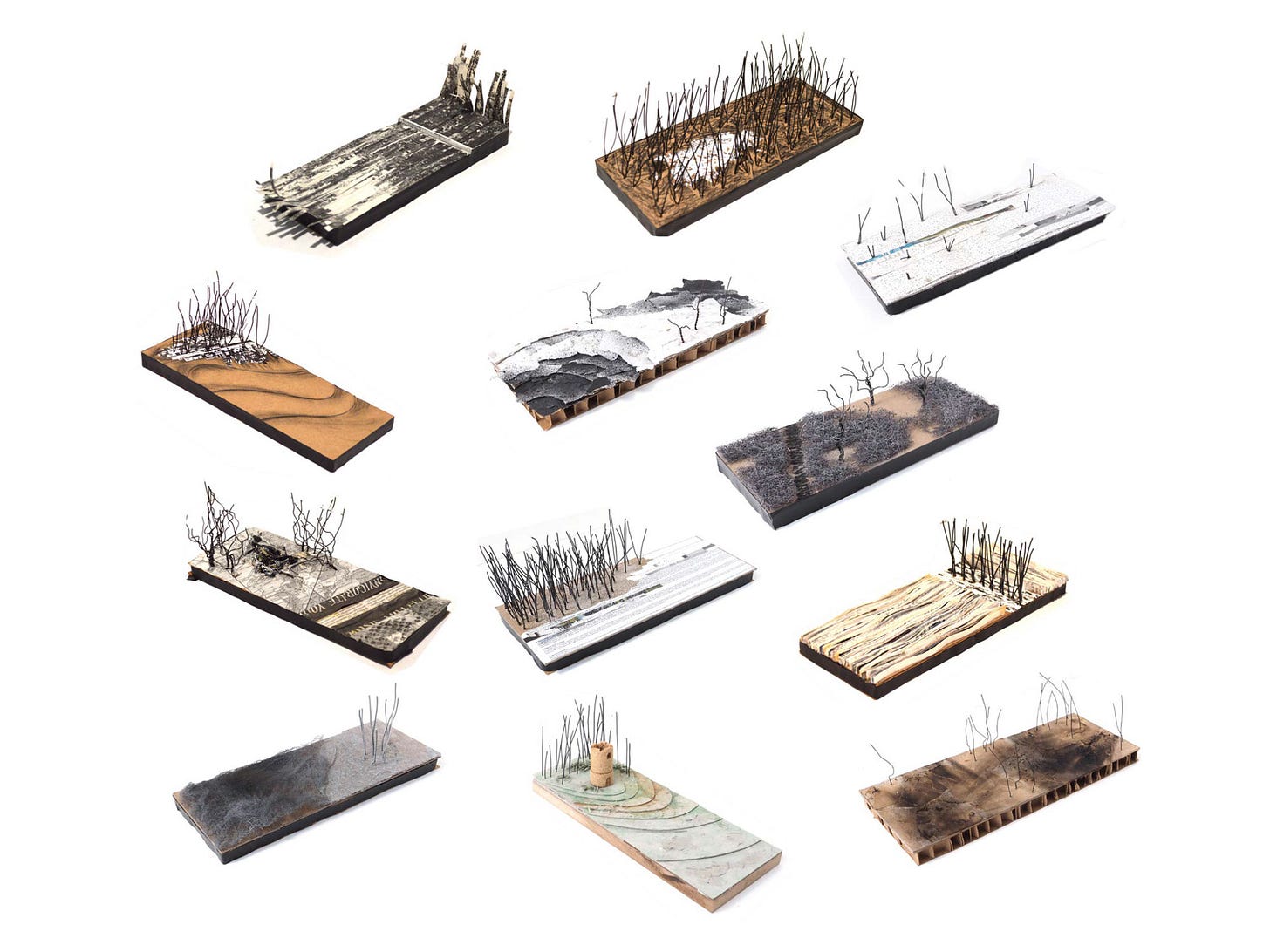

We asked the studio participants to imagine and design a series of prototypical interventions that could support both the ecological goals of the BDAWMP, accommodate development, and increase landscape coherence. We began with a series of landscape representation and vocabulary-building exercises. We quizzed participants to define over 100 landscape typologies. Each chose 6 terms from the list of quiz terms and created a 1:200 model of the landscape typology. We defined the modeling materials: honeycomb board for the base, monochrome newsprint or Kraft paper for texture, and wires and mesh for trees and shrubs. We mounted the finished models {Lexicon Models} on the wall of the studio as a visual library.

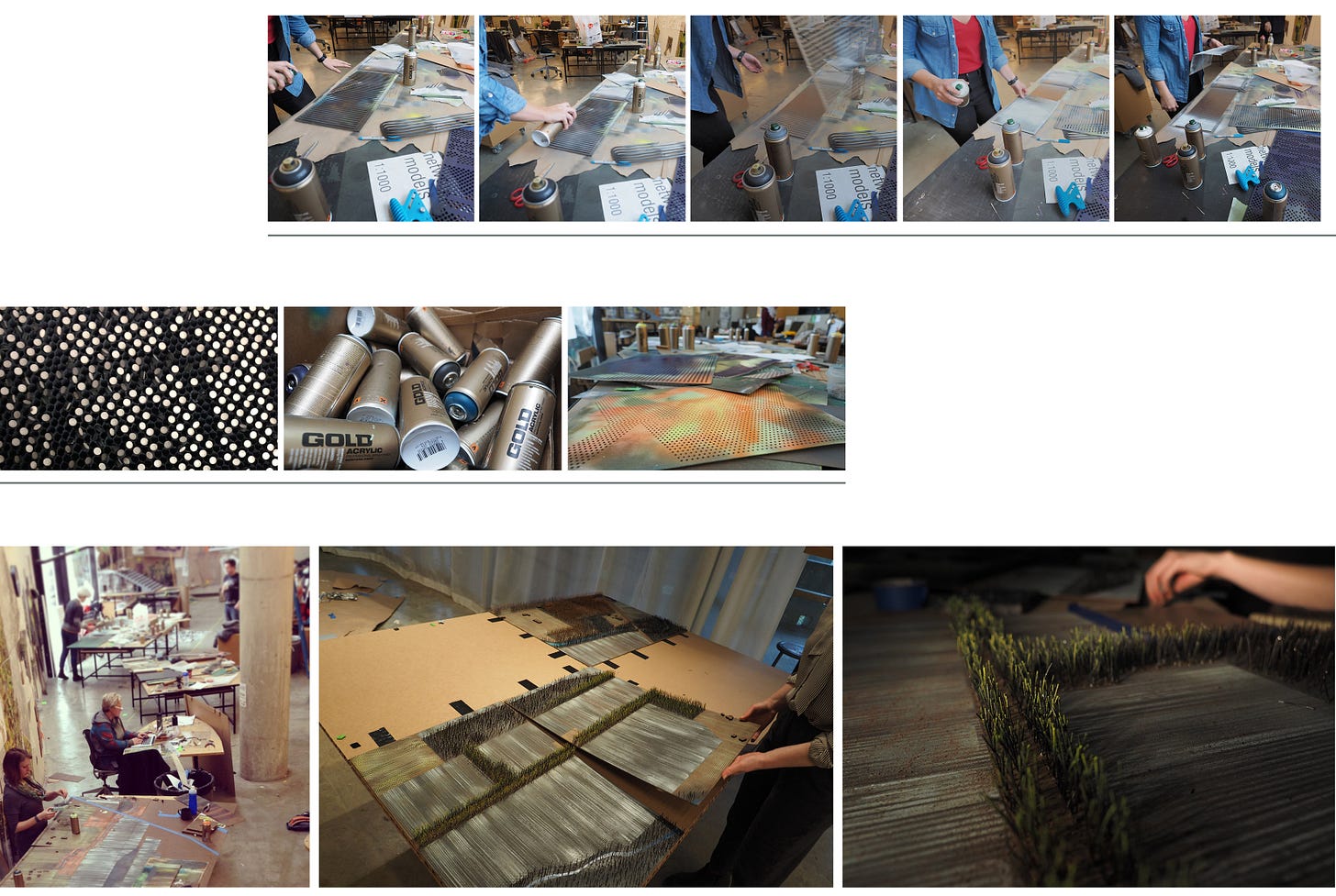

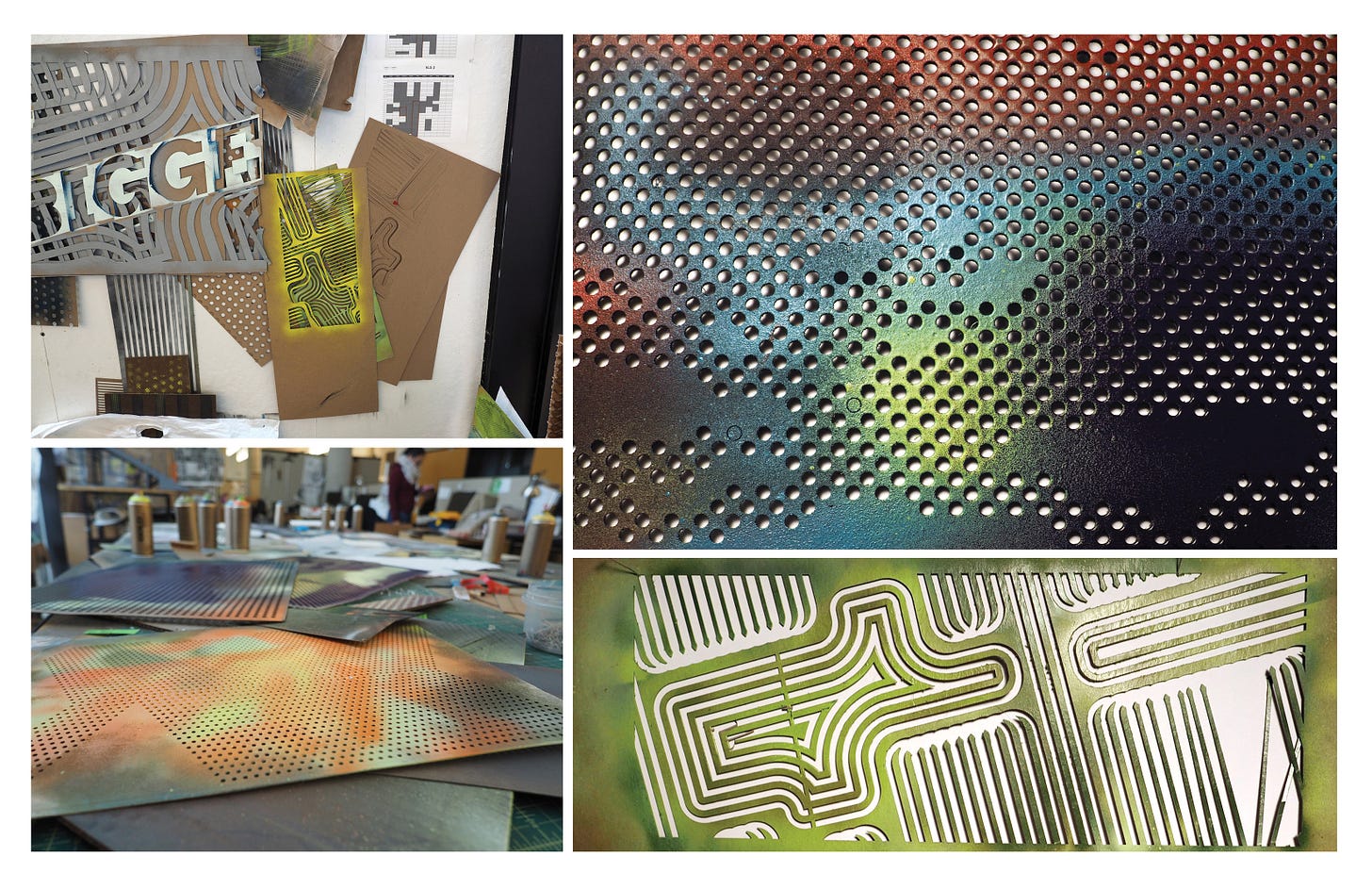

Next, we asked participants to invent new drawing techniques. Each student made a series of value studies from light to dark: 10 iterations of textures in 10 steps from dark to light. Their techniques were diverse: they tried stippling, burning, hatching, soaking, dripping. They made and hacked tools, and pushed the levels on the laser cutter to induce glitches.

Participants integrated the mark-making experiments with the lexicon studies by creating models depicting borders between land uses within the Big Darby watershed: between residential development and creeks; agricultural fields and woodlots; wetlands and recreation areas. A small group created a series of analytical models depicting stages of historic agricultural patterns of development.

Landscape architect Michel Desvigne served as a senior critic during the studio and visited several times for group critiques. Together we analyzed his work in regional landscape planning, particularly the proposals for Euralens in Lens, Liévin, Loos-en-Gohelle, France, and Rive Droite, in Bordeaux. In these proposals, landscape patterns and character are amplified through smaller-scale design interventions. The earthwork, planting, and editing of existing landscapes are established to accommodate future development. Desvigne describes the establishment of landscape scaffolds as prefiguration landscapes.

In our analysis of Desvigne’s work, we saw how we might combine a prefiguration landscape with the BMPs prescribed in the BDAWMP. We called these interventions BIG-MPs: management practices that include the added requirement of reinforcing landscape character in addition to solving for watershed improvement goals.

BIG-MPS

Participants created study models of enhancements to landscape edges and in-field treatments. Dubbed Bigger Management Practices (BIG-MPs), these management practices include the added requirement of reinforcing landscape character in addition to solving ecological, watershed, or farming issues. Using diverse implementation strategies that could be realized through a range of public-private partnerships, they tested the BIG-MPs at 1:200 scale for their potential to shape and define the greater landscape and addressed the priorities beyond those specified in the BDAWMP, including (1) riparian reinforcement, (2) preserving the open fields, (3) enclosing development with forestry, (4) providing recreational access, and (5) developing a stronger ‘sense of place.’

To expedite the production of models and drawings for the exhibition, one team created standardized mark-making tools using the laser cutter and woodshop. These toolmakers taught the mark makers how to create textures at a range of scales. The “tool makers” made stencils for spray-painting the models using a laser cutter. The “mark makers” rotated and combined the stencils to create richly layered patterns.

Studio teams addressed multiple scales including the neighborhood / farm (1:1000), transect (1:3000), and regional (1:10,000). They used physical modeling to look at how specific BIG-MPs combinations in the agricultural and suburban matrix of the watershed. From strategic over-planting along a rural road to encourage reforestation of subdivisions, widening of hedgerows to include bike paths or the creation of riparian wetlands, we saw that small practices could “scale up” to accomplish larger aims of regional coherence.

The atmosphere in the studio was collaborative, open, and experimental. We rearranged the studio with large worktables and large stockpiles of modeling materials; the tables were places to work, converse, experiment, and gossip. With hundreds of models in the studio, one could reach for a study model to quickly communicate a concept to an individual or group. Design iteration and gallery production in the studio was visible, tactile, and collaborative, unlike many environments where participants work individually at workstations.

Hybrid methods of landscape representation can unite the precision and reproducibility of digital tools with the inflection and invention of handicraft, collective production, and improvisation. In this studio, we challenged two orthodoxies in pedagogy. In the planning portion, we looked at how small-scale interventions could affect the larger region. In representation, we used digital tools to make tools for modeling and drawing techniques that required dexterity and personal artistry. Most significantly, our Inversion of the typical approaches resulted in a significant improvement in studio culture and cohesion.